Why Use Investigative Cases?

Cases provide meaningful contexts for study.

Investigative cases enable students to use their prior knowledge and their own interests to choose a meaningful problem for study. Learners construct new knowledge based on what they already know (National Academy Press, 2000).

"Start with the student's experience . . . and relate the subject matter to things the student already knows." (pp. 65-66)

(Shaping the Future: New Expectations for Undergraduate Education in Science, Mathematics, Engineering and Technology, NSF, 1996.)Learners come "to formal education with a range of prior knowledge, skills, beliefs and concepts. This affects what learners notice, how they reason and solve problems, and how they remember."

(p.10)(How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience and School. National Research Council, National Academy Press, 2000.)

Students learn geoscience in context as they employ scientific information and methods to investigate and resolve - at least partially - realistic, complex problems. When learning occurs around a specific problem, there is an increased likelihood that this learned material will be better retained and more easily applied to similar situations (Brown et al., 1989, Schmidt, 1983). While students may never face the exact problems under study, they gain experience using scientific approaches to work out reasonable solutions to situations that exist in their world. This experience is potentially transferable to the unique problems they will face in their own lives.

Cases initiate problem based learning for student-directed exploration.

In investigative case based learning, the case problem comes first in the instructional sequence.

Learners use the case to brainstorm a set of questions they will try to answer. Students become more aware of what they know and what they need to know. They thus become more directed in their reading and more motivated in subsequent lectures, labs, and discussions. In fact, they are learning in just the way most of us learn - they have a problem or question first.

Cases require the development of skills necessary for collaboration and lifelong problem solving.

(Shaping the Future: New Expectations for Undergraduate Education in Science, Mathematics, Engineering and Technology, NSF, 1996.)

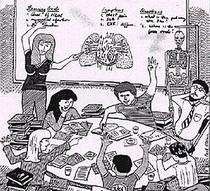

In the Harvard medical case-based PBL approach, students worked in groups of 8-10 with a "tutor." The group met regularly to discuss a case based on a real patient or situation. The figure on the left was drawn by a medical student to illustrate a typical session (Atebara, 1987).

Students read part of the case out loud, then discussed the elements presented thus far in the case. They generate hypotheses, list their outstanding questions, and developed a learning agenda -- issues they agreed to pursue before their next meeting. This phase of case study is one in which students are actively engaged and working together to brainstorm issues, share what they know, and develop their plans for learning.

The "instructor" has several roles (though to the student eye it may seem he does little): facilitates discussion, helps students explore their thinking and reasoning without leading them, and helps with group dynamics. The chalkboard belongs to the student during case discussions. Students take on roles we commonly think of as teacher roles: deciding what to focus on, developing questions, leading the discussion, using the board to keep notes, make drawings, or list learning issues. During case discussions, students are actively engaged in interpreting the case, proposing problems and possible solutions, brainstorming, and using resources. (Note: Resources to support student learning are frequently in the room - books, images, models, etc. In this 1987 figure, what is noticeably missing is the ubiquitous computer, computer tools and simulations, and access to the Internet!)

Cases are complex and require multidisciplinary approaches.

There is a tendency for learners to compartmentalize content and process knowledge by discipline - an unintended result of declaring a major and the resulting stepwise curricular approaches in undergraduate education. This is diminished as students draw from multiple resources in the sciences, mathematics, social sciences, and other disciplines to work with the case.

In addition to these benefits for learners, investigative cases also provide flexibility for instructors.