Assessing the impacts of video in Geoscience education

What do we want to know?

How do we know if the video we use in our courses is an effective teaching tool? What kind of assessments could we design to help us answer this question?

Participants at the Spring 2014 virtual workshop on Designing and Using Video in Undergraduate Geoscience Education compiled the following information to show their recommended organization and structure for conducting rigorous and formal assessment of video use in geoscience education.

Questions to address:

- How effective is video compared to reading?

- Pre- and post-inventory questioning --what is the impact of video on learning?

- How do students make use of the videos?

Assessment Design

The design of an effective assessment program depends on how videos are used in a course. For the purpose of this description, we will assume we are discussing the use of short videos (3-15 minutes) that are viewed online, outside the regular meeting of an introductory geoscience course. We will describe a case where videos are systematically incorporated into a course and are created to be viewed either weekly (or per textbook chapter or course module), or prior to all class meetings.

1. Does viewing of videos result in student learning?

- Students complete short pre/post quizzes online before/after viewing each video.

- Students complete a pre-test early in the semester and the same exam as a post-test after viewing of the final video.

- Students complete a pre-test early in the semester and those questions are then embedded in exams throughout the semester.

The latter condition makes it more straightforward to present the exam questions in a reasonable amount of time after the content is discussed in the course. In addition, the inclusion of the questions on an exam may result in students taking them more seriously than if they were on a quiz (regarded as a less significant contribution to grade) or a pre/post-test which often does not count toward a grade.back to Top

2. Does viewing of videos result in an improvement in student learning over not showing videos?

This condition requires that we have data on a control class that does not feature videos to compare with the treatment case that does include videos. In its simplest form, we might examine learning by some student volunteers after observing a video on a topic compared to learning that occurred after reading a passage of a textbook on the same topic. A more challenging study might compare a course that is taught for one semester without videos, and then videos are added for a second semester.

In either case, we would use a pre/post-test or a pre-test and embedded exam questions in both the control and treatment classes and compare results. This also assumes some common starting point, such that students will score similarly on the pre-test. That may be true if there is some consistency in the characteristics of students in each sample population, and if the class sizes are large enough to avoid the impact of a small handful of particularly high/low performing students. For example, contrasts in demographic characteristics such as gender, age, academic rank (freshmen vs. juniors), or major (STEM vs. humanities) might influence the incoming performance levels.

Some other aspects to consider:

- Should we use a classroom management system to track how students in the treatment conditions interacted with the videos? For example, some students might ignore the videos; others might review them in a cursory fashion. Is it necessary to exclude data collected from students who decide not to view the videos?

- Should we assess how much time is spent on each topic featured in the videos compared to in the control class? Could it be that students are simply doing better in the treatment class because they are spending more time on the material (combination of video + in-class review)? Does this matter? (That really depends on your research question – Do you want to compare overall student learning from all aspects of the course or do you want to consider if students learn more from video vs. lecture on the same material?)

- We should have well-defined grading rubrics that would achieve consistent grading results if we are using short answer questions.

3. Which method of interacting with videos results in the greatest improvement in student learning?

Instructors may seek to use videos in a variety of ways, some of which may be more successful in improving student learning than others. For example, videos could be used:

- As supplemental materials that are provided to students as a learning resource or exam preparation materials, but without any specific assigned tasks associated with course grades.

- As weekly post-class assignments that may or may not cover material presented in class. These assignments would be equivalent to conventional homework and would contribute toward a course grade.

- As daily pre-class assignments that cover material that would not otherwise be discussed in class. These assignments would be paired with online activities that would contribute toward a course grade.

There are opportunities to follow up on these out-of-class activities with in-class conceptests, using clickers or small group tasks. The proportion of the course grade that is associated with these assignments may influence the amount of effort students apply to reviewing the videos.

Effective assessment questions

Regardless of which research question an instructor might attempt to pursue, we should be careful to consider the validity and reliability of the assessments being used. A key step here is in matching the learning objectives associated with the video to the assessments that students are expected to complete after viewing.

To address reliability, we would wish to know that the questions would be answered consistently by students in a given course. This could be done by assigning the same pre-test twice, a week apart, and determining if the scores were similar and questions arranged in a similar order of difficulty. We could ensure construct validity by having a panel of experts review a video and confirm that the proposed assessments actually measured the learning objectives for the video.

Suggestions

Be sure to use multiple answer methods. For example, a question on a clip about deposition of sediment in a river may be "I am able to better understand the physical mechanisms occurring in this geological process." For this question you may have student respond with options like Strongly Agree, Agree, Barely Agree, Barely Disagree...etc. You may then add to this by asking "In 1 or 2 sentences explain why you feel this way." or "In what way did the video help clarify what was in the text?"

- Bank of Possible Survey Questions for Assessing Use of Instructional Videos (Acrobat (PDF) 33kB Aug29 14)

Examples of ongoing assessment

In Fall 2013, I created two videos on Geologic Time for students to watch while I was out of town. (One video is attached, The Geological History of Earth (MP4 Video 32MB Feb11 14), one of my first attempts at video creation). I posed the following anonymous survey questions to my class a few weeks later:

- Were they helpful?

- How did you learn differently using them vs. a typical class?

- How could we make them better?

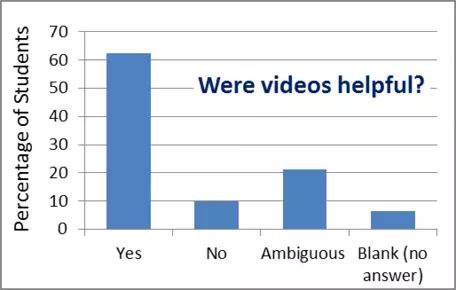

Generally, 62% of students said yes, the videos were helpful, 10% said no, the remaining 28% of students either left the answer blank or their answer was too ambiguous to interpret as a positive or negative response.

While most students stated that they thought the videos were helpful, a little more than a quarter of the class (28%) stated that they preferred the face-to-face class to the videos as it was more interactive, gave them opportunities to ask questions, or just found it more engaging. However, 25% of responding students liked the opportunity to pause the video presentations and to have the time to work at their own pace to process information and take notes. 8% responded that they learned the same way as in class while another 8% believed that the videos allowed them to learn differently and provided a new perspective. About 31% of students either didn't compare the videos to the face-to-face class or provided other answers. For example, some students found it challenging to watch the videos in their dorm setting due to the distractions from their peers, although they also noted that they had to concentrate more and pay closer attention.

Finally, there were relatively few comments about how to make the videos better. Those that did respond suggested adding examples, making the videos more interactive or adding more assessment activities or quizzes.

This "assessment attempt" was for my first online summer geology course. What follows is an Excel sheet that includes two of the questions I asked that actually pertain to the videos I made. The first tab references the PowerPoints that I did through Camtasia to include audio and annotations. The students seem to like having access to both the video presentation as well as the plain Power Point; they found each useful for different reasons. The second tab references all the demonstration videos and audio Power Point videos I made for students to complete the online labs. Nearly all the students said that having access to that prep material gave them more confidence to do the labs on their own.

- Mahlen Online Assessment Attempt (Excel 2007 (.xlsx) 11kB Feb20 14)

A quick summary of voluntary, anonymous student feedback questions regarding the use of video lectures and video tutorials on use of software to do geoscience (e.g., Excel, Google Earth). Small N, and I see a pretty large variability on the video lecture item from course to course despite using the same video lectures.

- Brudzinski Course Video Feedback (Excel 2007 (.xlsx) 10kB Feb21 14)

Additional resources

- Online

- International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning (website unavailable)

- The Development and Validation of a Survey Instrument for the Evaluation of Instructional Aids (Acrobat (PDF) 312kB Feb9 14)

- Reusing learning objects in three settings: Implications for online instruction. Conceição, S., Olgren, C., & Ploetz, P. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 3 (4). (2006)

This paper has an example of a very simple survey instrument. - In print

- Impact of multimedia learning modules on an introductory course on electricity and magnetism, T. Stelzer, D.T. Brookes, G. Gladding, and J.P. Mestre. American Journal of Physics, v.78, #7, p.755-759. (2010)

- Instructional video in e-learning: Assessing the impact of interactive video on learning effectiveness, D. Zhang, L. Zhou, R.O. Briggs, and J.F. Nunamaker, Jr. Information Management, v.43, #1, p.15-27 (2006)

- Evaluating a web lecture intervention in a human-computer interaction course, J.A. Day and J.D. Foley. IEEE Transactions on Education, v.49, #4, p.420-431. (2006)

- Comparing the efficacy of multimedia modules with traditional textbooks for learning introductory physics content, T. Stelzer, G. Gladding, J.P. Mestre, and D.T. Brookes. American Journal of Physics, v.77, #2, p.184-190. (2009)

- Evaluation of Evidence-based practices in Online learning: A meta-analysis and review of Online learning studies, B. Means, Y. Toyama, R. Murphy, M. Bakia, and K. Jones. US Department of Education. (2010)