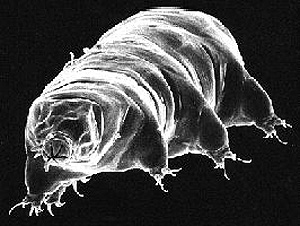

Tardigrades (Water Bears)

Created by Sarah Bordenstein, Marine Biological Laboratory

Strange is this little animal, because of its exceptional and strange morphology and because it closely resembles a bear en miniature. That is the reason why I decided to call it little water bear.

- J.A.E. Goeze (Pastor at St. Blasii, Quedlinburg, Germany), 1773

What is a Tardigrade?

Tardigrades (Tardigrada), also known as water bears or moss piglets, are a phylum of small invertebrates. They were first described by the German pastor J.A.E. Goeze in 1773 and given the name Tardigrada, meaning "slow stepper," three years later by the Italian biologist Lazzaro Spallanzani. Tardigrades are short (0.05mm - 1.2mm in body length), plump, bilaterally symmetrical, segmented organisms. They have four pairs of legs, each of which ends in four to eight claws. Tardigrades reproduce via asexual (parthenogenesis) or sexual reproduction and feed on the fluids of plant cells, animal cells, and bacteria. They are prey to amoebas, nematodes, and other tardigrades. Some species are entirely carnivorous! Tardigrades are likely related to Arthropoda (which includes insects, spiders, and crustaceans) and Onychophora (velvet worms), and are often referred to as a "lesser known taxa" of invertebrates. Despite their peculiar morphology and amazing diversity of habitats, relatively little is known about these tiny animals. This makes them ideal research subjects for which students and amateur microscopists may contribute novel data to the field.

Where to Find Tardigrades

Tardigrades can be found in almost every habitat on Earth! With over 900 ( This site may be offline. ) described species, the phylum has been sighted from mountaintops to the deep sea, from tropical rain forests to the Antarctic. Most species live in freshwater or semiaquatic terrestrial environments, while about 150 marine species have been recorded. All Tardigrades are considered aquatic because they need water around their bodies to permit gas exchange as well as to prevent uncontrolled desiccation. They can most easily be found living in a film of water on lichens and mosses, as well as in sand dunes, soil, sediments, and leaf litter.

How to Find Terrestrial Tardigrades

- Collect a clump of moss or lichen (dry or wet) and place in a shallow dish, such as a Petri dish.

- Soak in water (preferably rainwater or distilled water) for 3-24 hours.

- Remove and discard excess water from the dish.

- Shake or squeeze the moss/lichen clumps over another transparent dish to collect trapped water.

- Starting on a low obejctive lens, examine the water using a stereo microscope.

- Use a micropipette to transfer tardigrades to a slide, which can be observed with a higher power under a compound microscope.

Tardigrades in Extreme Environments

Tardigrades have been known to survive the following extreme conditions:

- temperatures as low as -200 °C (-328 °F) and as high as 151 °C (304 °F);

- freezing and/or thawing processes;

- changes in salinity;

- lack of oxygen;

- lack of water;

- levels of X-ray radiation 1000x the lethal human dose;

- some noxious chemicals;

- boiling alcohol;

- low pressure of a vacuum;

- high pressure (up to 6x the pressure of the deepest part of the ocean).

How do they do it?

Tardigrades have adapted to environmental stress by undergoing a process known as cryptobiosis. Cryptobiosis is defined as a state in which metabolic activities come to a reversible standstill. It is truly a death-like state; most organisms die by a cessation of metabolism. Several types of cryptobiosis exist, the most common include:

- anhydrobiosis (lack of water);

- cryobiosis (low temperature);

- osmobiosis (increased solute concentration, such as salt water);

- anoxybiosis (lack of oxygen).

The most common type of cryptobiosis studied in tardigrades is anhydrobiosis. Anton van Leeuwenhoek first documented cryptobiosis in 1702, when he observed tiny animalcules in sediment collected from house roofs. He dried them out, added water, and found that the animals began moving around again. The animalcules were likely nematodes or rotifers, other types of cryptobiotic animals. Tardigrades can survive dry periods by curling up into a little ball called a tun. Tun formation requires metabolism and synthesis of a protective sugar known as trehalose, which moves into the cells and replaces lost water. While in a tun, their metabolism can lower to less than 0.01% of normal. Revival typically takes a few hours, depending on how long the tardigrade has been in the cryptobiotic state.

Live tardigrades have been regenerated from dried moss kept in a museum for over 100 years! Once the moss was moistened, they successfully recovered from their tuns. While tardigrades can survive in extreme environments, they are not considered extremophiles because they are not adapted to live in these conditions. Their chances of dying increase the longer they are exposed to the extreme environment.

References

Learn more about Tardigrades with this collection of resources including informational websites, primary literature, and educational activities.

Additional Resources

For additional resources about Tardigrades, search the Microbial Life collection.