Trail Guide to Hyalite Peak, Bozeman, MT

By Tom Beers and Tyson Berndt, geology majors, Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University

"Keep your sense of proportion by regularly, preferably daily, visiting the natural world." -- Catlin Matthews

Introduction

The Hyalite Peak Trail is located just south of Bozeman, Montana in the heart of the Gallatin Mountains. The Gallatin Range is comprised of Archean metamorphics, Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary rocks, and Eocene volcanics.This trail traverses approximately 8 miles over some of the most unique and interesting terrain that Montana has to offer. The Hyalite trail itself is concentrated in an area that was once subjected to a rich and violent volcanic past. While trekking through the forest, many signs of this ancient environment can be seen in the form of columnar jointing, debris flows, and volcanic rocks. Aside from volcanics, geomorphologic features are also abundant. Previous glacial activity has removed hundreds of thousands of cubic meters of rock to the Gallatin Valley below and, because of this scouring of the landscape, we are rewarded with an ample supply of waterfalls, sinuous canyons, and steep cliffs.

Traveling to Hyalite

The Hyalite area is just 30 minutes from Bozeman and is open year round, but the best time for viewing the local geology begins in late spring. If a trip to the summit of Hyalite Peak is on the itinerary, visiting in mid to late summer is recommended. From Bozeman, travel south on 19th street for approximately 7 miles and then turn left onto Hyalite Canyon Road. Once you have turned, it is 9.5 miles to Hyalite Reservoir and another 3.5 miles to the trailhead. As you travel up the canyon, be sure to keep an eye out for exposed Archean gneiss as well as the Flathead Sandstone, Wolsey Shale, and Meagher Limestone. View this map for directions to the Hyalite Peak trailhead (Acrobat (PDF) 1.3MB Nov18 09).

Step by Step Trail Guide

The hike to Hyalite Peak is 7.5 miles in length and has an elevation gain of 3,450 ft. Setting aside 8-9 hours round trip is recommended in order to reach the summit. Once at the top you are treated to a 360-degree view that allows one to see the Absaroka, Gallatin, Madison, Tobacco Root, and Bridger (Acrobat (PDF) 8.1MB Nov23 09) mountain ranges. Hyalite Lake, which sits in a cirque just below the peak, is a hike that will take roughly 6 hours round trip. As always, plan for inclement weather when traveling into the backcountry. The first part of the trail is a gentle climb, and sections of it are paved or graded so that it is wheelchair accessible up to Grotto Falls. The trail steepens in the upper reaches of the valley as you approach the "wall of death"--a steep final pitch with many switchbacks just before arriving at Hyalite Lake. Share the trail and be careful--the trail is used by hikers, trail runners, mountain bike riders and horse riders. The following is a list of sites that lie close to the trail or within a short walk. Many waterfalls are within close proximity to the trail, or along a spur of short length.

Perhaps the most compelling features of the Hyalite Lake/Peak hike are the series of cascading waterfalls that can be seen from the trail. Here is a sampling of the falls, and an accompanying map to show their locations. You can download a PDF version of these waterfall locations. (Acrobat (PDF) 990kB Nov18 09)

The Amphitheater

After hiking through the sub-Alpine forests, the first set of cliffs you encounter is an area known as the Amphitheater. This resistant ridge formed as a single large cooling layer of an andesitic lava flow. These rocks exhibit a fracture pattern known as columnar jointing. This feature is formed as the lava cools and contracts, creating a polygonal jointing pattern.

The Hyalite Waterfalls

Grotto Falls

Arch Falls

Silken Skein Falls

Champagne Falls

Chasm Falls

Shower Falls

Apex Falls

S'il Vous Plait Falls

Alpine Falls

Hyalite Lake

Coming up and over the last set of switchbacks, Hyalite Lake is a welcome site, sitting at the base of the surrounding volcanic cliffs.

Hyalite Peak

Continuing past Hyalite Lake, Hyalite Peak looms another 1.5 miles in the distance. The trail traverses through beautiful high Alpine meadows. The trail can be pretty muddy from snowmelt, and snow may still be present on the north facing headwall late into the summer. Walk gently across these delicate Alpine meadows!

Beyond Hyalite Peak to Windy Pass

The Gallatin Crest Trail continues south to the northern of Yellowstone Park, and provides superb access to beautiful Alpine wilderness. This area is home to mule deer, elk, and grizzly and black bears--carry your bear spray and be "bear aware"! The trail can be quite rubbley and rough in some places, and be aware that there is very little water available except for snowmelt, a few seasonal springs, and a more reliable spring at the Windy Pass cabin some 18 miles to the south. From the Hyalite Peak trailhead to Windy Pass is the route of the famous "Devil's Backbone" trail run (25 miles one way, 50 miles out and back). This trail is also a very popular (and challenging) route for mountain bikers. Here is a collage of photos of what you'll see on the trail from Hyalite Peak to Windy Pass.

Geologic Setting

For a detailed view of the geologic setting, observe the Gardiner 100,000 Quadrangle Geologic Map from the Montana Bureau of Mines (this map can be downloaded as a PDF, or can be purchased as hard copy from MBMG). For further reference here is a Geologic Time Scale version.

The Hyalite Canyon area is located in the northern section of the Gallatin Range which, on a much larger geologic scale, is part of the Wyoming Archean Province (Mogk et al., 1992). The Wyoming Archean Province is composed of some of the oldest rocks on the continent, and rocks in the Gallatin Range have yielded ages as old as 3.2 billion years (using the U-Pb zircon method). In her Master's Thesis, Karen May (May, 1985) described these rocks as being predominantly quartz and feldspar bearing gneisses, metamorphosed basalts, with minor metasedimentary rocks. The basement rocks that are currently exposed at the surface were once buried as deep as 25 kilometers (~15 miles), and experienced temperatures as high as 750oC and 10 kilobars (over 10,000 atmospheres) of pressure! These rocks are well exposed on the Hyalite Canyon Road from the Gallatin National Forest boundary south to the Moser Creek area, north of Langohr Campground areas. These rocks contain some of the best "hard rock" climbing routes in the area!

These basement Archean metamorphic rocks are covered by more than 4,400 feet of Paleozoic and Mesozoic layers of sandstone, shale, and limestone (Weber, 1965). That's equivalent to stacking three Empire State Buildings on top of one another. According to Todd (1969), these sedimentary layers were approximately 10,000 feet thick in the southern part of the Gallatin Range and were subsequently removed by the erosive power of wind, water, and ice. Evidence for this lays in the fact that some of the Eocene Absaroka Volcanic rocks rest directly on top of the Archean metamorphics. The only way for this to occur is for the previous layers of sediment to be completely weathered away from the scene prior to deposition of the volcanic rocks. Just imagine the span of time it would take to carry away all of that material! Check out the stratigraphic column for Montana:

The Eocene (~56-34 million years ago) Absaroka Volcanic rocks that dominate the landscape lie on top of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic sediments (and locally on the Archean basement). These volcanics were the result of massive outpourings of epiclastic (gravel, sand, and mud deposits consisting of older rocks; these are major debris flow deposits known as lahars), some volcanic ash fall deposits (these are pyroclastic rocks) and relatively rare andesitic lava flows (Todd, 1969; Chadwick, 1970). This volcanic region stretches from Bozeman, Montana, 150 miles southeastward into Wyoming (Chadwick, 1970). The Eocene Absaroka Volcanics are part of a massive volcanic event that impacted most of the northwestern part of North America, including the Challis Volcanics of central Idaho, San Poil Volcanics of north central Washington, and the Montana Alkali Province that lies in the northern and eastern part of the state. The Absaroka Volcanics have an eastern belt that is more potassic in composition, and a western belt that is more sodic in composition. Eruptive centers have been documented in the northern Gallatin Range, Emigrant Peak in Paradise Valley, Electric Peak in the northwest corner of Yellowstone National Park, Mt. Washburn in the central part of Yellowstone, and Sunlight Basin on the eastern of Yellowstone near Cody, WY. Here is a reference map that illustrates the extent of the Absaroka Volcanics (produced by Dr. Todd Feely, Dept. of Earth Sciences, Montana State University).[b rlear]

The volcanics situated in the northern Gallatin Range are more than 6,000 feet thick, and are, for the most part, resting horizontally or dipping gently to the southeast (Chadwick, 1970). The volcanic history of the area is discussed in greater detail in the following section. Volcanic units include extrusive rocks (volcanic ash and lava flows), intrusive rocks (dikes and sills), and massive debris flows (lahars).

The initial structure of the Gallatin Range was established during an episode of mountain building called the Laramide Orogeny which began roughly 65 million years ago. This type of mountain building was caused by immense compressional forces from tectonic plate interactions that created high angle reverse fault zones. The compressive forces basically split the Archean basement rocks into pieces, some of which moved up and some of which moved down (Levin, 2006). As these large sections of basement rock were uplifted, overlying sedimentary layers were pushed up producing overturned and folded layers of rock, and these uplifts were subsequently eroded to their present levels of exposure. Resultant features included domes, basins, monoclines, and anticlines. This particular faulting is thought to have developed by drag and friction as the eastward trending Farallon plate scraped the underside of North America's cratonic margin. The mountains we see today are also the result of repeated episodes of Cenozoic extensional "normal faulting" (Levin, 2006). Examples of these two styles of faults are illustrated in the figure below. The landscape we see today is the result of erosion by glaciers, rivers, and surficial "mass wasting" processes that continue to sculpt the surface of the Earth. For more detailed information concerning Laramide deformation in the Gallatin Range, refer to Erick Miller's graduate thesis located in the Montana State University Library or Dr. David Lageson's interpretation of the structural evolution of the nearby Bridger Range (Lageson, 1989).

Volcanism

The Absaroka Volcanics produced voluminous outpourings of lava, ash and volcaniclastic sediments that originated from two northwest trending belts of eruptive centers named the Eastern Absaroka belt and the Western Absaroka belt (Chadwick, 1970). The entire Absaroka Volcanic province is composed of ~30,000 cubic km of basaltic (flowing) and rhyolitic (explosive) rocks that cover an area over 23,000 square km in northwestern Wyoming and southwestern Montana, constituting the most substantial Eocene volcanic field in the Northern Rocky Mountains (Feeley, 2003). During a mountain building cycle named the Laramide Orogeny, crustal deformation created zones of weakness within the cratonic (basement) layer which in turn produced channels through which magma could move, thereby forming intrusive and extrusive rocks. The Absaroka Volcanic province is dotted with these ancient eruptive centers and the Hyalite area just happened to be one of them (Chadwick, 1970). One of the most interesting characteristics of this volcanic province is that the Eastern Absaroka belt is more potassic in makeup than the Western belt. Further explanation of this can be explored by reading the works of Todd Feeley and Robert Chadwick, listed in the reference section below. The composition of the lavas, and the types of volcanic deposits seen in the Absaroka Volcanics indicates that the original volcanoes were probably stratovolcanoes that probably looked and acted very much like the volcanoes in the "ring of fire" that surrounds the Pacific Basin (for example Mt. St. Helens in Washington state)--complete with the steep sided "snow cone" shape, alternating layers of ash and lava, dangerous pyroclastic eruptions, and production of huge debris flows (lahars)!

Fallout: Volcanic Tephra

Tephra is the term used to describe all of the clastic materials that are ejected from a volcano and transported through the air. These include volcanic dust, ash, cinders, scoria, pumice, bombs, and blocks (Bates, Jackson 1984). As these particles settle out, some are fused together, creating a formation known as welded tuff.

Lava Flows and Columnar Jointing

Columnar jointing is formed when a lava flow cools quickly, from the outside of the flow to the center of the flow. This causes the rock to contract as it becomes more dense which in turn causes tensional stresses. If these stresses exceed the tensile strength of the rock, it will fracture. The fractures occur at right angles to the surface of the lava flow. This is why the columns are vertical in outcrop, as they were cooled from the top and bottom inward. Jointing also forms at 120 degree angles to one another around the point of contraction. This forms the hexagonal column that we see today.

Debris Flows and Layering

These deposits seen at Silken Skein falls can be easily distinguished from one another by the change in clast sizes. These are actually different pyroclastic flow deposits that sourced from eruptive centers around southwest Montana (see figure above). Some are normally graded while others are inversely graded. A normally graded deposit will have the largest and heaviest clasts at the bottom of the deposit, while inversely graded deposits have the largest clasts at the top. Pyroclastic flows begin with the collapse of an eruption column, much like the one that Mt. Saint Helens produced in 1980. As the column collapses tephra (ash, pumice, hot gases, etc.) are pushed out laterally. The flow hugs the ground under the force of gravity while at the same time spreading in width, sometimes flowing at speeds up to four hundred and fifty miles per hour. These flows are also extremely hot, at temperatures up to one thousand degrees Celsius! Aren't you glad you weren't hiking this trail while these flows were occurring?! For an in depth look at the various types of debris flow layering that occurred in the Hyalite area, examine Margaret Hiza's work listed in the reference section. The deposits that are seen at Silken Skein were formed by processes very similar to those that took place during the eruption of Mt. St. Helens in 1980.

Present Day Volcanism Reminiscent of Hyalite

The processes of sedimentation in volcanically active regions are quite unique because they occur very rapidly and include very large volumes of material (Hiza, 1994). By looking at present-day volcanic deposition, the mechanisms of sediment transportation of the past can be better understood. One of the best places to go for information and archival footage regarding volcanic processes is the Cascade Volcano Observatory and the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory Photogallery. Each of these sites provides photos and interpretations of processes that help to visualize and better comprehend the forces that are required to change the face of the earth.

Geomorphology and Landscape Evolution

Glaciation of Hyalite Canyon

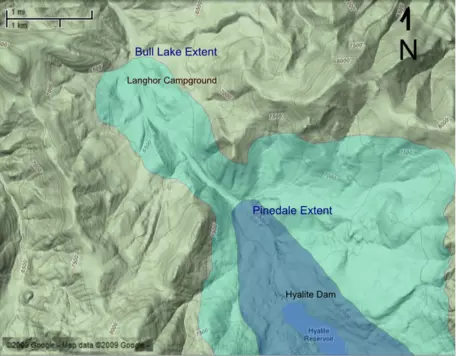

Hyalite Canyon has been glaciated multiple times, and two of Hyalite's glacial advances have been mapped by Mark W. Weber in 1965. These two advances have been given the general names "Pinedale" and "Bull Lake" in the Rocky Mountains. The Pinedale maximum advance of the Hyalite Glacier was approximately 16 to 24 thousand years before present, while the Bull Lake advance was around 150 thousand years before present. Evidence of glaciation is seen throughout the Hyalite basin in erosional features such as the U-shaped valley and numerous depositional features known as moraines (deposits of unsorted, unconsolidated debris that sheds off the end of a glacier. "Terminal" or "recessional" moraines form because glaciers act as conveyor belts, transporting eroded rock and soil debris. When the rate of melting of the glacier is almost the same as the rate of flow of ice down the mountainside, the glacier deposits its materials at its end, forming low, long ridges of this loose, unconsolidated, and unsorted debris).

The Bull Lake advance of the Hyalite Glacier flowed all the way down the drainage to the present day location of the Langohr Springs Campground which you will pass on the way to the trailhead. The ice from this advance was up to one thousand feet thick in some spots, such as the present day location of Hyalite Reservoir, and still approximately eight hundred feet thick where Grotto Falls is currently located. Glacial moraines can be seen on the east ridge adjacent to the Langohr Springs Campground.

The Pinedale moraines can be seen from the road on the drive up to the Hyalite trailhead. There are three distinct moraines that lay directly east of the Hyalite Reservoir Dam. The three sharp crested ridges to the south of Wild Horse Creek are these deposits.

There is also a deposit in the east cirque just below Hyalite Peak which is worth observing if one has the time. It is the most recent deposit of the Hyalite Glacier, referred to as the neo-glacial advance by glacial geologists, that is an advance that occurred in the last few thousand years (a picture of the deposit can be seen above).

Various other glacial features can also be seen throughout the drainage, such as glacial erratic boulders, glacial polish, striation, and cast and groove marks. Some large boulders which lay in the valley seem out of place or are anomalous, because they are not the same type of rock as that which surrounds them. They are also too large to have been moved by the present day creek from up valley. This is rock that was entrained by the glacier and moved from its place of origin to the present day location.

.

Glacial polish, striation, and cast and groove marks are a result of ice that has picked up "tools," such as small rocks, that have then been ground into the bed of rock over which the glacier was flowing. The ice can carry, roll, or stick and slip these tools leaving lines called striations, cast marks, or imprints of the tool. Striations preserve the flow of the glacier at the time the tool was moved over the bed, while casts show the rolling of the tool, and grooves demonstrate a stick and slip nature.

Pro Talus Ramparts

Funny name, but simple process! These are features that one can see at the base of steep talus slopes, or loose rock slopes. They are ridges that parallel the slope at the hill's toe and are normally very coarse and full of boulders. Pro talus ramparts form as a result of winter snow accumulation in the high mountains. Slopes in the Gallatin range can get on average 30 ft of snow or more, and the lower reaches of these slopes have more snow than the upper parts due to sluffing and avalanching. This has the effect of making the hillside extend out into the basin or cirque farther, which makes the slope more gentle. When a rock falls on this surface, it slides or tumbles along this new slope formed by the snow, which deposits the rock at the slope's toe. Since this toe is more basinward than the slope's toe without snow, the rock is deposited in the form of a new ridge past the talus slope's toe. Check it out!

Landslides

Notice anything out of the ordinary as you drive to the Hyalite trailhead? On Hyalite Canyon Road there is an active landslide within the first 3 miles after the turn off of south 19th street. This landslide has been caused by deep fluvial incision (a large amount of stream erosion), which has oversteepened the walls that contain Hyalite Creek. This has caused the ridge to collapse catastrophically, as it continues to pile debris on the road year after year. This landslide is under turbulent flow, meaning that it is not moving as a sled over snow (such as laminar flow in a glacier), but more like a stream in which the material mixes. This causes "drunken trees" which are named for their random orientation and erratic angles at which they lean.The photo below shows a landslide that occurred in Yellowstone Park, similar to the slide in Hyalite Canyon.

Hill Creep and Frost Creep

Hyalite canyon has other types of soil movement: hill creep and frost creep. Hill creep is the slow, downslope movement of material caused by gravity. This process occurs in the upper few feet of soil, and decreases rapidly with depth (Ritter, Kochel, Miller, 2002). The existence of soil creep can be observed by the presence of curved trees that vegetate the landscape. These trees look like pistols at their bases, due to the fact that the tree has rolled downslope and then straightened up again, hence the name, pistol butted trees. The trees look this way because the soil under them is actually creeping downhill overtime. This movement is normally a result of steep slopes and water laden soil, which reduce the cohesion and internal friction of the soil body. Frost creep is the downslope movement of particles resulting from the expansion and contraction of ice within the soil (Ritter, Kochel, Miller 2002). As the temperature drops, ice crystals form within the soil and then expand. This expansion dislodges soil particles, making them susceptible to gravity when the ice thaws.

Solifluction

Solifluction is a process in which water logged soils creep downhill over an impermeable or permanently frozen soil layer. This process occurs during the melt season, or spring months, when melting is at its peak and large amounts of water are contributed to the ground. The top layer of soil retains a large portion of this water, sometimes reaching its maximum amount, which is the saturation point. This added weight causes the layer of soil to mass waste, or move downhill under the force of gravity. We can see these deposits of solifluction today in Hyalite Canyon and actually almost everywhere. They are parallel lobes that move downslope perpendicular to the slope. The trail to the peak actually crosses a few; be sure to observe them on your way towards the summit.

Avalanche Deposits:

In the spring, wet snow avalanches occur because of an increase in snow density which causes the snow to slide down the slope. These avalanches can occur via point releases, that is, starting from a single point and widening downslope, or they can also pinwheel, or build like a snowball as they roll. These avalanches can involve snow all the way down to the underlying rock and soil. When avalanches of this nature occur, they often entrain rocks off of the talus that underlies, and deposit them on the sides and at the terminus, or end of the avalanche. After the snow melts, the rock deposits are all that is left, which we see in the summer as levees which connect at the bottom. These features can be seen in the east cirque of Hyalite peak, directly above Hyalite Lake. The Google Image shown is in the west cirque of Hyalite Peak.

References and Further Reading

Alt, David, and Hyndman, Donald W., 1995, Northwest Exposures- A Geologic Story of the Northwest: Montana, Mountain Press Publishing Company, 456 p.

Alt, David, and Hyndman, Donald W., 1986, Roadside Geology of Montana: Montana, Mountain Press Publishing Company, 427 p.

Bates, R. L., and Jackson, Julia A., 1984, Dictionary of Geological Terms Third Edition: New York, Anchor Books, 571 p.

Chadwick, Robert A., 1982, Igneous geology of the Fridley Peak quadrangle, Montana, Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology: Geologic Map 31, 9 p., 1 sheet, 1:62,.

Chadwick, Robert A., 1970, Belts of Eruptive Centers in the Absaroka-Gallatin Volcanic Province, Wyoming-Montana: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 81 p. 267-274.

Feeley, Todd C., 2003, Origin and Tectonic Implications of Across-Strike Geochemical Variations in the Eocene Absaroka Volcanic Province: The Journal of Geology, Vol. 111, No. 3, p. 329-346.

Feeley, Todd C., and Cosca, M.A., 2003, Time vs. Composition Trends of Magmatism at Sunlight Volcano, Absaroka Volcanic Province, Wyoming: GSA Bulletin, Vol. 115, No 6, p. 714-728.

Fritz, William J., 1985, Roadside Geology of the Yellowstone Country: Montana, Mountain Press Publishing Company, 149 p.

Hiza, Margaret M., 1994, Processes of Alluvial Sedimentation in Eocene Hyalite Peak Volcanics, Absaroka-Gallatin Volcanic Province, Southwest Montana [Masters Thesis]: Bozeman, Montana State University, 167p.

Kochel, Craig R., and Miller, Jerry R., and Ritter, Dale F., 2002, Process Geomorphology: Illinois, Waveland Press Inc, 560 p.

Levin, Harold, 2006, The Earth Through Time, Eighth Edition: New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, 547 p.

Lindsay, Charles R., 2002, Petrogenesis of Eocene Calc-alkaline Magmatism at Electric Peak and Sepulcher Mountain, Absaroka Volcanic Province, Montana and Wyoming [Masters Thesis]: Bozeman, Montana State University, 155 p.

May, Karen A., 1985, Archean Geology of a Part of the Northern Gallatin Range, Southwest Montana [Masters Thesis]: Bozeman, Montana State University, 91 p.

Miller, Erick W. B., 1987, Laramide Basement Deformation in the Northern Gallatin Range and Southern Bridger Range, Southwest Montana. [Masters Thesis]: Bozeman, Montana State University, 78 p.

Mogk, D., Mueller, P., and Wooden, 1992, The Nature of Archean Terrane Boundaries, an Example from the northern Wyoming Province. Precambrian Research, v. 55, p. 155-168.

Todd, Stanley G., 1969, Bedrock Geology of the Southern Part of Tom Miner Basin, Park and Gallatin Counties, Montana [Masters Thesis]: Bozeman, Montana State University, 63 p.

Tysdall, Russell G., 1966, Geology of a Part of the North End of the Gallatin Range, Gallatin County, Montana [Masters Thesis]: Bozeman, Montana State University, 95 p.

Weber, W. Mark., 1965, General Geology and Geomorphology of the Middle Creek Area, Gallatin County, Montana [Masters Thesis]: Bozeman, Montana State University, 86 p.

![[creative commons]](/images/creativecommons_16.png)