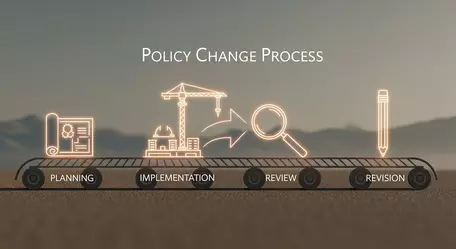

Theme 4: Approach policy change as a process

NOTE: The LCC4 project was launched to advance teaching effectiveness and evaluation at colleges and universities across the country. This meant different things to different people and institutions involved in LCC4. Thus, the content of these pages does not reflect the views of all LCC4 members or their institutions.

In this page:

Introduction | Document and communicate | Support implementation and review adherence | Revisiting policy over time

The other three themes include:

Theme 1: Align » Theme 2: Strategize » Theme 3: Assign »

Introduction

Document and communicate

Although LCC4 institutions used different approaches to conducting policy changes, several made efforts to document the work as it progressed and communicate with stakeholders throughout the process. Clearly noting and broadly communicating the steps taken in the process of developing and implementing new policy helped change agents to stay on message through leadership changes. Documentation also provided evidence of the quality of the work (e.g., that input was sought from diverse stakeholders, that multiple sources of evidence were used), which helped to engender buy-in and respond to naysayers as policy was being implemented. LCC4 institutions shared information about policy changes and gathered input through multiple avenues from diverse stakeholders to help their communities prepare for, buy into, and respond to policy change. Having institutional leaders share key information and messages seemed especially powerful. Providing talking points to these individuals helped maintain consistent, shared messaging.

- At Georgia Southern University, the Ad Hoc committee tasked with establishing teaching evaluation policy met with the departments, college leaders, and the college governance committee to gather feedback on draft material. These meetings were important both for achieving the practical goal of improving the material and for creating space for colleagues to respond to the changes and air any concerns. The committee then synthesized the feedback and used it to fine-tune draft materials to better reflect the institution's context and consider faculty concerns. Ultimately, this process allowed for creation of policy that was deemed "good enough" to be adopted.

- In the process of making policy changes, change agents at the University of Oklahoma kept a timeline of key events and steps along the way to establishing the new teaching evaluation policy. The timeline helped ensure continuity through leadership changes. The timeline was also useful for responding to naysayers who questioned aspects of the change process (e.g., that input was sought, that changes were announced).

- Shortly after a new teaching evaluation policy was adopted at the University of Georgia, there were multiple changes in university leadership. The policy, including how the changes had been widely vetted and received widespread support, was not clearly communicated to new leaders, which resulted in mixed messages that had the potential to undermine policy implementation. This oversight was quickly identified, and steps were taken to clarify understanding of the policy among leadership, the rationales behind particular policy elements, and the timeline for the policy change work, including how stakeholder input was sought and resulted in policy refinements.

Support implementation and review adherence

When LCC4 institutions drafted their policy change narratives, they were making policy changes but had not yet assessed implementation and accountability. Because implementation and accountability are part of the policy change process, they require planning, milestone setting, and workload allocation.

- Once a new teaching evaluation policy had been established at the University of Georgia, it became readily apparent that faculty and administrators needed support in implementing the new policy. This led to the establishment of a "catalyzing action team," which is a cross-department, cross-college team of faculty members nominated by their department head (one or two per unit) tasked with and compensated for developing unit-level practices and procedures related to teaching evaluation. These individuals worked with their departments to create templates, guidelines, and other resources to support their faculty in reflecting on and using student experience survey results and carrying out self and peer evaluation of teaching.

- The University of Portland supported implementation and monitoring of policy on faculty compensation using a process that could be applied to changing teaching evaluation. First, a standing Faculty Compensation Committee of faculty and administrators, including the provost, was established to support implementation of faculty compensation policy and revisit compensation practices over time to ensure adherence to policy. Second, the committee was chartered with a clearly articulated philosophy about compensation, which was codified in the faculty handbook and could be used to guide decisions that were not anticipated by the original charge. Finally, the committee had well-defined goals for implementation of the new policy, including specific dates of adoption and a schedule of monitoring and maintenance tasks designed to update the system as needed.

- The University of Oregon has an institution-wide policy for teaching evaluation that each academic department has to adopt into their own departmental policies and has the opportunity to make the policy match their departmental teaching values. This is a part of an overall process for departments to update their policies to match faculty union collective bargaining agreements. The provost office offers templates, workshops, and stipended faculty positions to lead to policy revision work in departments.

Revisiting policy over time

In the process of working on policy changes, LCC4 institutions recognized the need to update policy more regularly to reflect current priorities and practices. For instance, some LCC4 institutions had not examined their teaching evaluation policy in 25 years. Although policy is expected to be more static and enduring than day-to-day practices, all LCC4 institutions were working to ensure that multiple entities are tasked with periodic review and updating of policy. Explicit acknowledgment that policy can and should be changed, especially if unforeseen issues arise, can relieve some of the pressure of establishing "perfect" policy.

- The University of La Verne has a standing Senate subcommittee, known as the Faculty Policies Committee, which is charged with monitoring policies in the Faculty Handbook and coordinating with administration if exceptions or changes are needed. The committee has standing meetings to which faculty can bring agenda items, including concerns about policy conflicts and lapses. The committee then reviews the relevant policies and practices and takes steps to clarify policy and communicate with administration. Thus, the committee serves both proactive and reactive functions, advising both faculty and administration on policy implementation in ways that are consistent with the spirit of the policy. When additional policy changes are needed, the Faculty Policies Committee drafts the proposed changes, which are then voted on by the Faculty Senate and Faculty Assembly. If both bodies pass the revised policy, the Board of Trustees must approve it before the policy is officially changed in the Faculty Handbook.